Deer Valley Golf Course, just past Barneveld on Highway 151 in southern Wisconsin, is a beautiful, daunting, textured course, a great pleasure to play if your game is under control; a great source of misery if not. It resides in the highlands and deep vales of that particular part of the world, a parcel of land that must have been terribly hard to farm, when once it was farmed. Colin and I played it again today.

Teeing off on the first hole, one dives down into a sharp crease of a valley, and then descends up a wide ski slope of a hill to--somewhere up there--a green. We duly teed off, with Colin's long drive getting pulled into the rough between the outward bound first fairway and the inward bound, parallel ninth fairway. I hit my second shot, from much further back from where Colin's drive landed, and drove the golfcart up to where he was comparing golfballs with the couple who were headed downward on the ninth fairway.

The woman peered at me, then said,

"Hello! Do you have a blog?"

Um.

"Yes, I guess I do."

"Is your name Bruce?" Ohoh.

"Yyyyeah..." Who would this be? Perfect strangers, these two. Yes I am Bruce, yes I have a blog. Why am I being asked this on a hillside on a golfcourse near Barneveld?

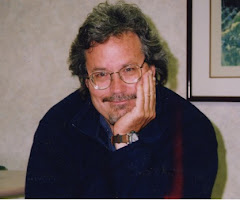

"My name is Mary; I spent last week with your wife at the Higher Things conference! I recognized you from your blog photo!"

Too weird. Later, alone, I asked Colin if I was that recognizable across a span of golfcourse rough.

"Yeah. The goatee, the robust grey hair...You're pretty recognizable."

Friday, July 31, 2009

Saturday, July 11, 2009

Vocation and the Sedir Bed

It has been a cool July; sky blue and the large shop windows opened inward to allow a breeze. Inside, the sedir bed has taken shape, a long low platform with drawers, nothing fancy, the work of a week. A Turkish quilt and imported pillows will flesh out the decor. My job is to simply give them a resting place.

I'm counting out the final things in my mind, the little project minutiae that do not make it onto the flat scripted plan but are there to be done: pilot holes counter sunk in pine planks; maple pulls turned and installed; drawer front edges veneered; drawer fronts fitted and installed,; exposed surfaces sanded. Finally, the marking of parts, and disassembly and then off to the finishing room.

My client I've had for many years. Our relationship started with refinishing a formal dining room of furniture, and has grown to the point where, when I drop by for a project, I get coffee, talk politics and culture, and take a tour of their rock garden. They've just returned from Cappodoccia, Turkey, where a niece lives in a cave, something in that dry country that is actually as interesting and comfortable as the image is strange . A land of caves. Deep in the cave home is a sedir bed, a low platform upon which sit sumptuous and comfortable mattress and pillows. Being smitten with it, and thinking of a little room in their home back home, they have purchased and shipped the requisite, floral, black and red Turkish pillows, and only require the platform itself, modified for American tastes. And so the email came to me, asking if I might be interested in building the platform, the Sedir bed.

The shop has recently been cleaned. Piles of wood cut-offs, neglected since last Summer's building projects (these furniture-making sprees seem to be a Summer occurence, going back years); a pile of wood chips behind the planer; table saw and post sander and jointer and bandsaw surfaces needing a good cleaning and lubrication. I had the son of a friend over to help with the project, a day's work of hauling wood chips out to the raspberry patch, cutting and stacking fireplace wood, and dragging the plywood cutoffs out to the burn-pile. So, some semblance of order, like a clean kitchen before the creation of a feast. Everything works better, tools are where they are meant to be, the mind is more orderly and at ease.

A lithe, dangerous orange and white teenaged cat wanders in, chasing his fancy and the hopes of little things to bat around, things to climb on, things to nibble. He gets promptly turned around and sent back out the door. He is not yet shop cat. I'll let some of that young feline energy dissipate before letting him loose among the fresh finishes, fine wood furniture pieces, and power tools.

A bit of lathe work. Turning drawer pulls goes like this: the first one is spontaneous and creative, following a pattern developed over many years but always with a little variation. All of the subsequent pulls are laborious, an effort of copying closely the first, spontaneous effort. Squares of maple are cross-cut on the table saw, diagonal lines drawn on one face to find center, then corners band-sawn off before a center pilot hole is drill-pressed, and finally onto the lathe, one at a time. I select four or five lathe tools from a motley collection of an unmatched dozen or so, sharpen them quickly on the vertical sanding belt, and get to work. When doing lathe work, you cut or you scrape. The cutting action takes more skill but is cleaner and very much more satisfying, a laying of the bevel of the tool against the wood and slowing rotating the cutting edge into the work. It is something like that satisfaction of learning to ski: first the [scraping] laborious snowplow, and later the slow evolution into [cutting] parallel skiing, culminating in perfect, blissful, controlled floating down a mountain. With lathe work, there are occasional very nervous events as one learns how to apply the tool to this swiftly rotating spindle or chunk of wood. The two maple pulls turn out well, and I'm off to the next little thing.

This shop and I have been together for 23 years. I built it after working out of a garage for two years,. Like all relationships, after awhile we have taken each other for granted. The shop was mine before I was the shop's. Some part of the angst of

difficult, sleep-denying problem jobs has rubbed off on this place, so that at times I haven't liked it at all. There is also this other thing: a deepening sense of attachment. So many pieces have come through here, to be mended, sanded, color matched, finished. And many furniture pieces have had their origin here, taking a shape from ideas, plans, rough boards, plywood. Perhaps it is a growing sense, finally, that I know what I am doing and can relax a little, trusting my experience and the vocational guidance of the holy spirit.

The Sedir bed, stained and finished, will go out at the end of next week, making room for the next collection of broken furniture in need of mending.

Sedir Bed, installed.

Wednesday, July 8, 2009

Rhetorical Theology

August Friedrich Christian Vilmar. I'm reading a book by a 19th Century German theologian entitled THE THEOLOGY OF FACTS VERSUS THE THEOLOGY OF RHETORIC. A little, light, bedside reading for the lay theologian.

According to Vilmar, "theologians of rhetoric" remind him of old BC Greek poets who rather than creating original forms wrote dense, polished, wordy verse. Cicero scorned them. He makes a connection between these "Alexandrian" poets and the rationalistic Christian theology of his own, German nineteenth century. "For more than thirty years authors are no longer read, but read about," he complains. In a rather fascinating chapter called Literature and Exegesis of Holy Scripture, he makes the case that this Alexandrian rhetoric has infected theology, with the result that the gospel is completely lost.

"An exegetical course by rhetorical theologians has the habit of opening a "scientific" discussion in which arguments and counter-arguments are weighted, opinions heard and rejected, views proposed and refuted, and all, or the highest ranking "scientific authorities" are allowed to speak. There is only one authority that does not regularly speak: The Word of God itself..."

Now it gets interesting:

..."And yet this should be the first task of an exegete, to make it a duty to set as the hearers' first task the reading of portions of Holy Scripture with a gathering and stillness of soul, and again, and again, and yet again, to read it without allowing one human word, not even one's own to interrupt. The divine word gradually takes on life and speech while at the outset it appeared dead, and it begins (in a most unfigurative sense) to speak with us, to us, in us. It shows us that it is not a speech put together from individual words, but rather a divine deed, that it is the Word, at once light and life, from which bright and ever brighter streams fall on every detail..."A gathering and stillness of soul. Vilmar actually compares the reading of scripture to the reading of really difficult, interesting ancient poetry, that of Pindar and Aristophanes.

"...Let them go to them without all the expositions, commentaries, and scholia. Let them read them seriously through three, four, and more times, despite all the difficulties of language and subject matter...Gradually, the whole product takes on a surprising life and intelligibility, and gives an enjoyment which can be weakened but never strengthened by subsequent use of commentaries...[This] was the source of great joy philologists took in classical antiquity, but Luther in Holy Scripture."It occurs to me that this deep, innocent, protracted reading of scripture is what is missing today from our church people (me included). There was a time when huge swaths of scripture were committed to memory by children of eleven and younger. It was the basis of much of their education in their early years. Vilmar testifies to his own training, while regreting that at the time of writing this emphasis had been lost:

"The foundation for this secure knowledge of scripture, sound in all its details, was laid in families and schools, but now no longer. The essentials were gained at the university. I call to mind only what we experienced, that all the dicta probantia [Biblical proof texts] in the original Hebrew and Greek text, besides that at least twenty to thirty Psalms, eight to ten chapters from Isaiah, the first three chapters of Genesis, and numerous sections of the New Testament (the Sermon on the Mount, chapters 14-17 from the Gospel of John, Romans 5-8, and other sections) were committed to memory in the original languages."I'm guessing, but it is likely that the sort of sermon heard by the parishioners in the above cartoon came from the "theology of rhetoric": intellectual word games that manage to entertain without offending "people like us."

Cartoon taken from The New Yorker Album of Drawings, 1925-1975.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)